My earlier article, “Signs of a renewed general crisis of capitalism,” focused on the important role the money commodity gold continues to play in the world capitalist economy—and indirectly in shaping world politics. Understanding that role is therefore crucial to a full appreciation of capitalist economic crises and longer-term political and economic trends.

The article also pointed to the changing role of the money commodity as a key factor, along with monopoly capitalism/imperialism (which had emerged in the latter part of the 19th century), in the first phase of the general crisis of capitalism starting with World War I and the Russian Revolution.

Further data has come to my attention (shown in the following charts) that reinforce and further illuminate these points.

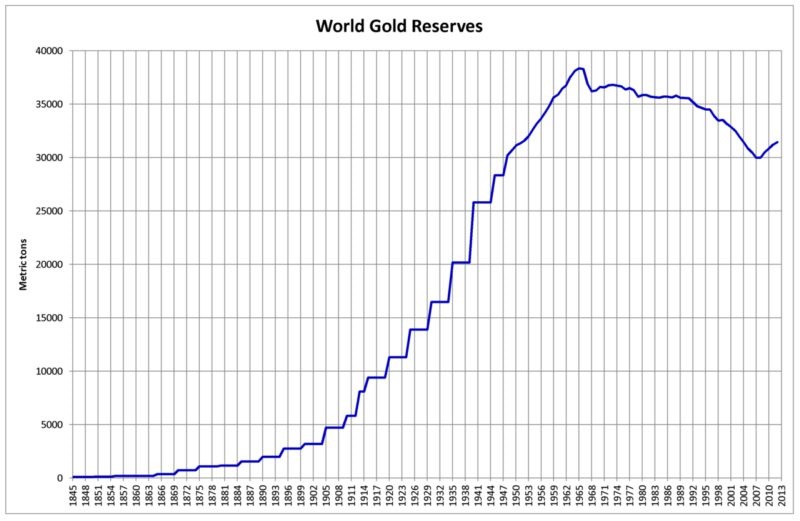

The first chart below shows the gold holdings of governments and central banks (so-called official, as opposed to private, holdings*) from 1845 to 2012. Except for brief intervals, during the entire period shown on the chart up to 1968 the U.S. dollar and other major currencies were directly or indirectly tied to gold at fixed rates of exchange. This was the “dollar-gold exchange standard,” the monetary system negotiated at an international conference held in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, in 1944). That system de facto died in March 1968 after the dollar’s fixed exchange rate with gold could no longer be maintained.

From 1934, after President Franklin Roosevelt had devalued the dollar by 40 percent, to March 1968, that rate was fixed at $1 = 1/35th of an ounce of gold. In other words, the dollar price of gold was maintained at $35 an ounce. Other major currencies, such as the British pound and the French franc were tied to the dollar, also at fixed rates.

In other words, these currencies represented (stood in for) gold at legally fixed parities, or exchange rates. Monetary and fiscal policies of central banks and governments had to be adjusted at different phases of the industrial cycle to maintain these relationships—though from time to time devaluations were carried out, usually to maintain or restore political stability.

Historic sea change in monetary policy

As is clear from the chart, a sea change occurred in the late 1960s tied to abandonment of the international gold standard. That standard had long been considered by virtually all bourgeois policy-makers and economists a necessary foundation of stable currencies and economies. That is until influential British economist John Maynard Keynes disputed the notion in the 1920s, arguing that depreciation of a currency might be necessary at times to avoid politically risky mass unemployment. It would be several more decades, however, before Keynes’s monetary theories would be implemented, and then only when bourgeois policymakers had no other choice.

Prior to the final abandonment of the gold standard, there never was a year that the official holdings of gold declined (see above chart). The policy was, rather, to incrementally increase these holdings in line with the actual and anticipated long-term expansion of the world capitalist economy and markets, and the resulting need to expand the means of exchange and payment in the form of gold-backed banknotes (dollars, pounds, francs and so on). Pragmatic policymakers understood that simply printing money while gold reserves and gold production** remained static was a recipe for destruction of the currency.

The first gold pool

The London Gold Pool was the pooling of gold reserves by a group of eight central banks in the United States and seven European countries that agreed in November 1961 to cooperate in maintaining the Bretton Woods System of fixed-rate convertible currencies and defending a U.S. dollar gold price of $35 a troy ounce by interventions in the London gold market.

The pool was established after the U.S. began to run a chronic balance of payments deficit following recovery of the European and Japanese economies following World War II. The United States pledged to provide 50 percent of the required gold supply for sale.

As indicated in the above chart, this effort successfully defended the dollar for six years, though after 1965, with escalating U.S. government deficit spending for the Vietnam War and “Great Society” social programs, official gold reserves began to fall sharply as the dollar came under increasing pressure. Finally, in March 1968, following the Tet Offensive in Vietnam, the gold pool collapsed and the U.S. was de facto forced off what remained of the gold standard.

At the same time, Lyndon Johnson, now widely hated as a result of the war (“Hey, hey LBJ, how many kids did you kill today” was a popular chant of the anti-war movement), announced that he would not seek a second term as president.

The second ‘gold pool’

For several years, official gold holdings began to climb again, but then, beginning in 1970, went into a prolonged downtrend lasting until 2007—the start of the Great Recession. This prolonged downtrend was mainly due to an attempt—successful for about two decades beginning in 1980—by the U.S. government and Federal Reserve to revalue the dollar after its precipitous fall in gold value of some 90 percent in the 1970s. This was done especially to benefit wealthy bondholders, who had seen comparable losses in their dollar-denominated holdings over the decade.

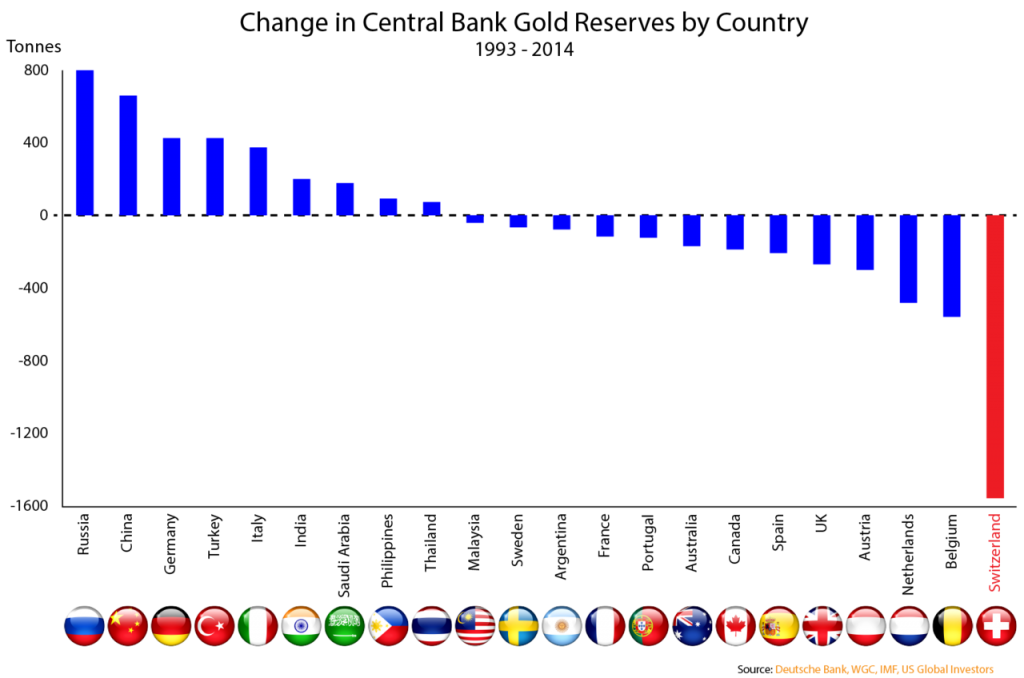

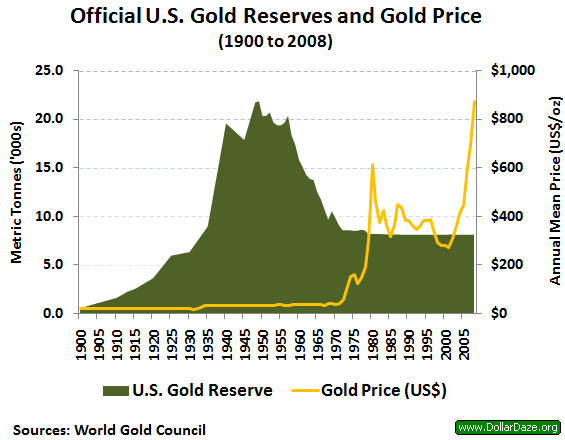

The next chart shows the reductions in official gold holdings by more than a dozen countries at the behest of the U.S. empire in the period 1993 to 2014. The chart after that shows the official U.S. gold reserves from 1900 to 2008. Note that the U.S. held on to all its gold after 1980 while its “allies” (aka satellite imperialist and client states) reduced their holdings by as much as nearly 1,600 tons in the case of Switzerland. A number of other countries failed to cooperate in this endeavor, building up their reserves by as much as 800 tons in the case of Russia and many hundreds of tons in the case of China.

In addition to the sizable reductions in official gold holdings indicated in the above charts, holdings of private investors, which greatly expanded in the course of the 1970s, were steadily reduced, especially in the 1990s, once it became clear to all but dogmatic “gold bugs” that the dollar had stabilized—further driving down the dollar price of gold until the dramatic reversal in 2001 (shown in the chart below).

As shown in the “World Gold Reserves” chart above, most countries began once again to increase their gold reserves after 2007, reflecting mounting nervousness regarding the stability of the U.S. dollar. Again, China and Russia have been leading the effort—wishing to reduce the risk of an all-out collapse of the U.S. currency.

Rising gold production but sluggish recovery

As my earlier article emphasized, rising gold production has in the past generally coincided with economic expansion and relative capitalist prosperity. A rate of growth of the global gold hoard that exceeds the rate at which the production of non-monetary commodities is growing allows the capitalist market to expand without hitting what Marx called the “metallic barrier” resulting in a major overproduction crisis.

This has remained the case since the end of the international gold standard. Instead of being tied to gold at a legally fixed parity, currencies now “float” in gold value—that is, they remain tied to gold through the metal and foreign-exchange markets but at constantly fluctuating values. That is all that has changed. Gold, because of its unique combination of physical qualities, continues to play its essential role as universal measure of value and is not, as is widely believed, “just another commodity.”

But this still poses the question of why the sharp rise in global gold production since 2009 to a new all-time peak in 2015 has not resulted in a more robust upturn in the U.S. and world economy. Instead, we have seen a prolonged period of weak expansion in the imperialist and many “emerging” economies—what some bourgeois economists call “secular stagnation”—and in several countries, such as Greece, Venezuela and Brazil, deep recession. What accounts for this?

I believe part of the answer is the “strong dollar” resulting from a tightening of Federal Reserve monetary policy. (See my article “Strong dollar destabilizes world economy” explaining this.)

Another part of the answer is that much of the increased global gold production is accounted for by China, which is now the largest gold producer globally by far, and much of that increased production goes directly into China’s official reserves rather than onto the metals market. (Available numbers on China’s gold production and holdings are not considered completely reliable, but some recent reports, such as here and here, appear to confirm this trend.)

Over the past several decades, China accumulated several trillions of dollars’ worth of U.S. treasuries (bonds, notes and bills) as a result of the huge trade deficit the U.S. has been running with China over the same period. The Chinese government is prudently building up its gold reserves at an accelerated rate to protect against a depreciation of these dollar-denominated assets.

The result is that a significant portion of China’s gold production does not come onto the gold market. If all of that production were to be dumped on the market, the dollar price of gold would likely fall sharply and commodity prices in gold terms would rise, stimulating economic activity. Instead, prices of primary commodities such as oil and copper have been in a pronounced downtrend, and the prices of commodities in general have been more or less flat. This is not what generally happens in periods of relative capitalist prosperity.

Objective laws in command

Capitalist politicians typically get blamed for cyclical downturns of the economy and claim credit for cyclical upturns, both of which the policies of their administrations have relatively little to do with. This blame game often determines the outcome of bourgeois elections—for example, the victories of Bill Clinton in 1992 and Barack Obama in 2008.

The stage of the industrial cycle may well determine the outcome in the 2016 election as well. Certainly an economic slump in the next several months would hurt Hillary Clinton’s chances, since she has tied her fortunes to President Obama’s record, and boost those of Donald Trump. The U.S. government now appears to be attempting to stave off a downturn until after the election, especially with the nightmarish prospect of a Trump victory causing the ruling political class sleepless nights. Only time will tell if the effort succeeds.

The same misconceptions apply in a longer-term sense to extended periods of relative prosperity or stagnation. For example, FDR’s reforms and Keynesian-style deficit spending are widely credited, along with World War II, with getting the U.S. out of the Great Depression. Republican politicians pushing neo-liberal (“conservative”) policies blame Keynesian-style deficit spending and “over-generous” and “harmful” (from the standpoint of the ruling class) social programs for the prolonged stagflationary crisis of the 1970s. Now latter-day Keynesian economists are coming forward to blame the current period of stagnation on the neo-liberal policies instituted by Ronald Reagan and his successors.

The truth is, as I tried to explain in my earlier article, that the capitalist economy, with its booms and busts and longer periods of relative capitalist prosperity and extended depressions, operates on the basis of objective laws that even the most powerful corporations, central banks and governments cannot for the most part—or for long—override.

During periods of relative capitalist prosperity—when prices in gold terms are rising—leaders of the workers’ movement are obligated to lead a fight for every gain possible, and it is possible to win gains and progressive reforms in such periods. When prices go into an extended decline and unemployment rises, the workers’ and progressive movements are thrown onto the defensive, and the central task becomes to defend previous gains. But until capitalism is replaced with socialism, the objective laws of the system will prevail in the end.

I believe that as a result of those laws, in particular those that relate to the role of money and drive the increasingly tyrannical and disastrous rule of finance capital, world capitalism has entered a period of renewed general crisis—a period of acute economic and political instability that will ultimately pose the question of which modern class will rule, and whether humanity survives the coming storms and achieves socialism, or self-destructs in a nuclear holocaust.

_______

*Wealthy capitalists typically keep five to 10 percent of their financial assets (stocks, bonds, real estate and so on) in gold as insurance against total loss of their capital in a crisis. During periods of major crisis, such as the 1970s, private capitalists boost their gold holdings, putting sharp upward pressure on the currency price of gold. Especially since abandonment of the gold standard, hedge funds and other big speculators jump into the market as a crisis approaches, forcing further sharp increases in the currency gold price and setting the stage for an all-out “run” on the currency that if not stopped would inevitably end in its complete destruction.

The classic case of such a hyperinflation was Germany in 1923. A run on the U.S. dollar began in late 1979 and was only halted when the Federal Reserve under Paul Volcker drastically increased short-term interest rates—“the Volcker Shock.”

The aftermath of this action was the early 1980s deep recession with its mass unemployment and widespread impoverishment. As explained in my previous article, that slump caused prices in gold terms to fall sufficiently to bring about a renewed long-term rise in the production of gold and an extended period of relative capitalist prosperity that economists have termed the “Great Moderation.”

**More specifically, the key relationship determining growth of the capitalist market is not production at any point in time of non-monetary commodities in relation to the production of the money commodity but rather the production of non-monetary commodities over some period of time in relation to the rate of increase over the same period of time of the global gold hoard (public and private).