In honor of the 126th anniversary of Harry Haywood’s birth, we’re reposting this article originally published on Liberation School in 2014.

Harry Haywood was a long time member and leader of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) and other communist organizations from the 1920s until his death in 1985. He was the key figure in developing and popularizing the concept that Blacks represented a separate “nation” inside the United States.

While Haywood merits almost no mention in many accounts of Black history, his theoretical innovations probably did more than any other one individual to frame the terms of the debate about the historical character of the “Black community.”

The “Black Belt thesis”

The “Black Belt thesis” established the oppression of African Americans as a “national question” of utmost importance for revolutionaries in the United States.

What became known as the “Black Belt” thesis has its roots in the conception of Black Americans initially conceived by Haywood and other communists of various nationalities in the Communist International.

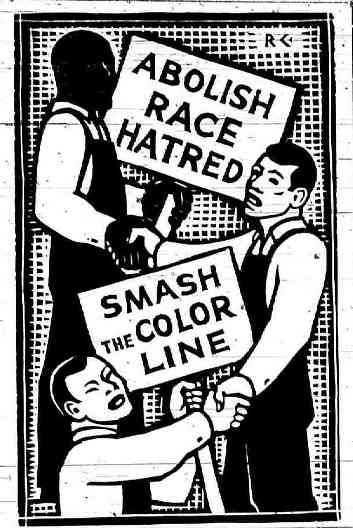

Communist Party cartoon from 1936. During this period, the CPUSA’s anti-racist militancy stood apart from nearly all other organizations with white members in U.S. society.

Basing itself on the conceptions developed by Lenin and grounded in the Soviet experience with oppressed nations, this theory held Blacks in America made up not simply a racial or ethnic group, but comprised an oppressed nation. The thesis was adopted at the Sixth Congress of the Communist International—under Stalin’s leadership—in 1928.

This conception did not mean nation in the sense of the “nation-state” as today’s common usage would suggest, but rather had its roots in the concept of how nation states were formed by capitalism. As feudalism gave way to capitalism, the new social system smashed the barriers of innumerable fiefdoms, and through a long process of war and market growth took people of different historical backgrounds and across relatively large areas and molded them into one people with a common language, national market, culture, etc. Each nation-state that developed in this way— the most common examples of this process being Western European countries, such as France and England—had a unique historical development.

Lenin’s traditional conception had held that “multi-national states” appeared in countries where the process of capitalist development had been uneven, where non-capitalist or semi-capitalist economic forms played major roles economically and socially. This held true for tsarist Russian empire, where the Romanov monarchs sought to introduce advanced capitalism, without making any changes to the country’s feudal character. Russia thus created a fusion of the most advanced capitalist methods, alongside the social structure and agricultural life of the 13th century. This historical unevenness created a multinational nation-state, spanning an entire continent, involving over 100 different distinct nationalities and ethnicities.

Haywood saw a similarity in the situation of African Americans. Although brought to America from many different ethnicities and cultures, the unique experience of slavery overtime forged Africans into a new distinct people. For Haywood, this was not only a cultural phenomenon—in which Blacks developed a common identity based on their common experiences and struggles—but also had a geographic basis. The transformation of Africans of disparate backgrounds into a common African American nation occurred over a defined land base in the Deep South where Blacks maintained a majority of the populace.

After the overthrow of Reconstruction, debt peonage in the south and the Jim Crow system further ingrained the super-exploitation of Blacks in the “Black Belt” south as a dominant and enduring feature of U.S. capitalism. The region in question, Haywood argued, in fact represented an internal colony. What followed from this was the notion that if Blacks made up a “nation” within the United States, they also had the right to self-determination—that is the right to form their own nation-state in the Black Belt South.

A full discussion of the Black Belt thesis and its modern relevance is far beyond the scope of this article. But in this author’s opinion, Haywood’s concepts still represent the best starting point to understand the Black “national question.” One can debate the south-centered “land base” of a potential Black nation, but one cannot debate the unique historical evolution of African Americans as a distinct nation within a multi-national state.

It is also worth mentioning that, unlike almost all other theories propagated on this issue since Harry Haywood first addressed it, Haywood’s concepts were based on a detailed and systematic class analysis of the actual conditions of Blacks in America. His skillful use of the historical materialist method sets a high standard for all Marxists to follow.

Distinctions from Black nationalism

Harry Haywood did not develop his theoretical conceptions on the Black nation out of any desire for Black separatism; he was totally committed to the idea of a united working class party. However he realized only a party that bases itself on a life and death struggle against white supremacy could overcome the obstacles to class unity. Such a struggle was necessary to earn the trust of the Black masses on one hand, and to break white workers away from ruling class ideology on the other.

While Black communists collaborated with all sorts of other forces in the mass struggle, Haywood made a clear distinction about the program of communists. The communists’ efforts to win working-class leadership of the Black liberation struggle and their advocacy for socialism as the only resolution to national oppression, brought them into conflict with bourgeois Black leaders of both the “integrationist” and “nationalist” type.

Haywood subjected both the bourgeois integrationist trend and the nationalist trend in the 1930s Black community to a class analysis. The integrationist NAACP and Urban League, represented by “successful businessmen, top-echelon leaders, upper-bracket educators, and local politicians,” typically commanded leadership of the Black movement, due to their deep linkages to Wall Street and white philanthropic organizations.

On the other hand, the nationalists were rooted in the Black “ghettos” among “small businessmen, the intelligentsia, professionals and the like” and expressed the desires of the Black petit-bourgeoisie, stunted by modern imperialism, to control the economic life of Black urban communities. In conditions of crisis especially, Haywood noted, the nationalists’ appeal to race solidarity or Back-to-Africa programs had the capability of attracting large sections of the Black poor, for whom the integrationists provided no economic answers.

Haywood asserted it was necessary for communists to recognize the anti-imperialist, revolutionary potential and historical legitimacy of the Black nationalist movement. At the same time, Haywood warned the Party that the militancy of its petty bourgeois stratum “is very misleading” (424) and repeatedly pushed the Party to not make the opposite mistake of “surrendering to the propaganda of local nationalists.”

Haywood’s point is further reinforced by the fact that “Black capitalist” schemes have on several occasions found support amongst the most reactionary elements of the white community, from the Ku Klux Klan to Richard Nixon, who proclaimed in 1968 that many Black militants merely wanted a “piece of the action” rather than an overturning of the social system.

One good example of Haywood’s departure from petty bourgeois Black nationalism is in the “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaigns of the 1930’s, which took root in Harlem, Baltimore, Washington, D.C., and elsewhere. These campaigns, led by local Black nationalists who shunned work with whites, took aim at the white-owned stores that excluded Blacks from employment while selling products in the ghetto. Nationalist leaders called for the white employees to be replaced with Black employees at the targeted stores, a demand that quickly developed a significant following.

Haywood knew that the campaigns thrived on the “justly felt anger” of the Black working-class, but argued that “the ruling class was overjoyed with this type of movement” because it blurred the class line and “tended to quickly become anti-white.” They “directed the struggle against these small establishments, which had only a small fraction of jobs,” as well as white workers, and thus “the broad struggle of Black unemployed was diverted away from the large corporations located mostly outside the ghetto.”

Haywood argued that the Communist Party could not stand aloof from this struggle for Black jobs, instead calling for the Party to focus on a broader campaign, spearheaded by Black and white unionists, which did not call for the firing of any existing workers.

Many then and since have criticized the CPUSA for this, considering it an unnecessary concession to white workers that weakened the struggle. Ira Kemp and Arthur Reid, two nationalist leaders, were some of the leading critics of the CPUSA. They had started something known as the Harlem Labor Union, which won some jobs for the community by convincing store owners to hire Black workers at lower than the prevailing wage.

In contrast, Haywood’s tactics always started with the Party’s strategic outlook: building Black-white unity in the fight against both national and class oppression. Indeed, Haywood devoted a good deal of his political energies, as well as his later autobiography, to this fundamental question facing revolutionaries in the United States.

‘Black and white, unite and fight!’

Building class unity has never been an easy task. For one, white supremacy has long functioned as an unofficial state religion. Secondly, Black people in the United States face “special oppression” above and beyond the “normal” forms of oppression meted out by capitalist society; the resistance to these forms of oppression will thus take a unique form.

Finally, looking over the country’s history, a pattern emerges in which Black people surge forward in struggle, become the engine for radicalism in society as a whole, but are crushed by the combined forces of the ruling class before a sizable enough section of white workers recognize their common interests with the Black freedom movement.

Liberals and nationalists tend to accept this pattern as inevitable and irreversible, but draw opposite conclusions: either that Black people should go slow and not demand so much (the liberal argument), or that Black people should focus on carving out spaces or states independent of the existing social order (the nationalist argument). Revolutionary Marxists support the right of self-determination, but also propose a different solution to the uneven development of political consciousness among different sectors: a fighting organization that has fused together the workers leading in each sector, maintains significant influence in each, and frames tactics that promote the common benefits of class struggle and Black liberation.

This perspective of promoting multinational unity is easy to uphold on paper, but must be fought for in practice. Stirring up racism among white workers has long been the most powerful weapon in the ruling class’s arsenal. Further, Haywood recognized that the nationalist sentiments of the Black working class inevitably would find some expression within the Party—a phenomenon that he warned against most emphatically in the Party’s 1934 Convention.

Haywood wrote:

“Just as the ruling class ideology of white supremacy had its influences on white comrades, it was not unusual that Black comrades would similarly be affected by petty bourgeois nationalist ideology. These moods were and sentiments were expressed in feelings of distrust of white comrades, in skepticism about the possibility of winning white workers to active support in the struggle for Black rights, and in the attitude that nothing could be accomplished until white chauvinism was completely eliminated. This latter was particularly dangerous because it failed to understand that white chauvinism could only be broken down in the process of struggle.”

The two trends of white chauvinism and petty bourgeois nationalism were not equivalent, but both “deviated from the line of proletarian internationalism” and needed to be tackled. As a leading Black member of the CPUSA, Haywood played his part in upholding the long-held division of labor in the communist movement with regards to national oppression: comrades of the oppressor nation would lead the fight against chauvinism inside the Party’s ranks, while comrades of the oppressed nation must combat narrow nationalist deviations.

Haywood stressed that any slacking on the part of the Party in leading the practical struggle among Black workers would disarm their ability to combat both considerable dangers.

Haywood recognized that multi-national unity is not a feel-good exercise, or simply a helpful secondary factor. Rather, a united working class is the only road to an overthrow of capitalism, which holds the only chance for the full liberation of the mass of Black workers, who constitute the vast majority of Blacks in America.

This is the legacy left to us by Harry Haywood: a critical and uncompromising dedication to the total liberation of Black workers, the working class, and humanity itself.